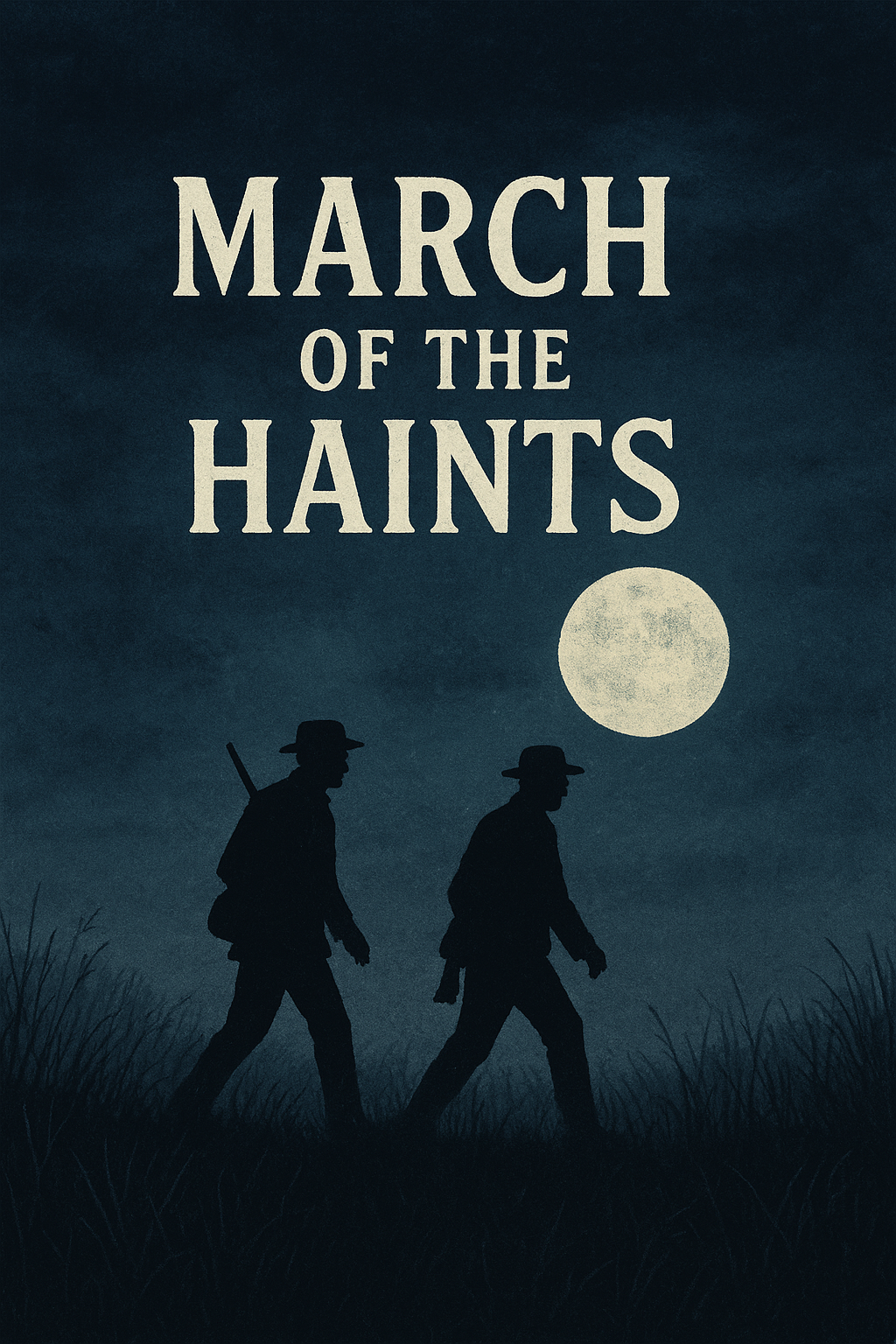

Grover and Monroe clomped through thigh-high grass toward the farm.

Cousins by blood. Brothers by friendship. Connected by adjacent plots of land. The young men had been close for as long as either could remember.

Folks knew that if you saw one, you'd likely see the other.

Tonight was no exception.

The two had stayed at Monroe's house longer than expected. Grover joined his aunt, uncle, and cousins for supper. At the table, he mentioned some boards on his father's pack house could use mending.

Kin helps kin. Monroe volunteered to lend a hand. The plan was for him to sleep over at Grover's house and get an early start on the repairs.

It was dark when the boys set out—their only light, a half moon. Its soft glow was appreciated but not needed. They knew the way like they knew each other's faces.

The air was cool. Enough weeks had passed that there was little concern of stepping on a snake. Other nightly critters would know to stay hidden or to skulk out of the way. They walked with assurance.

The pass through the field was uneventful until they saw the two other shadows approaching.

They heard them before they saw them—the unmistakable sound of feet.

Grover and Monroe stopped and exchanged a glance.

"Could be your brothers," Monroe said.

"Could be. Sure would be late for Cal to be up, though," Grover said back.

Calvin was 10. It wasn't like his parents to let the young ones stay up this late.

"Might be some of the Beesons," Grover said. "Maybe they're hunting a raccoon."

The Beesons were the closest neighbors that weren't family. They lived over a mile down the unincorporated unpaved road.

"Odd, they're coming this way," Grover thought to himself. "Why ain't they headed towards the woods?" He had treed the furry bandits before with his father.

Grover listened for any dogs, proof that the strangers were tracking something, but heard nothing shifting through the tall grass around them.

The shadows continued to come. They were fifty yards away.

"Why are they walking like that?" Monroe asked. His voice had dropped to just over a whisper.

Grover had noticed too. The two figures were walking side by side, their steps perfectly in sync.

"Looks like marching," Grover said.

They were. The two forms moved as one. Their sets of feet and knees rising at precisely the same time.

"Should I hollar at 'em?" Monroe asked.

Grover's answer shot out before he could stop it, "No." Something about this was making his skin crawl.

"Get down," he said.

"What?" Monroe asked.

"I said get down," Grover said. Monroe caught urgency in his cousin's voice.

They squatted and slowly lay out on their bellies.

The cousins waited for the figures to come closer.

The brogan boots landed not five feet away. Grover heard the crunch they made mixed with the soft rustling of wool britches rubbing together. The sound reminded him of something being scratched. Holding his breath, he looked up to see silhouettes. They both wore coats and appeared to have caps on. Something stretched across their backs, too small and thin to be a knapsack, part of it protruding out towards their heads.

If the moon had been full, Grover would have seen it was a rolled-up blanket.

However, his eyes needed no help identifying what the men had in their hands. Rifles.

He looked over at Monroe. Monroe stared back. The two of them came to the same reasoning—keep quiet.

The figures never paused. They moved past the shaken boys in a matter of seconds.

It was 20 minutes before Grover and Monroe moved. The boys remained silent, but both thought about how far they were from the safety of their farms.

They gradually stood up, turning their necks in the direction the figures had gone in. No sign of them. The darkness around them seemed less harmless than it had been before. A light breeze moved the tops of the grass, and Monroe fought the feeling that they were trapped in a sinking boat in the middle of a forbidding lake.

They began to run, reaching the farm before they found a reason to speak.

In bed, they talked about what they'd seen. Before falling asleep, the boys had begun to refer to the figures as soldiers.

Over the next few days, they told their story to family. Some listened and gave rational explanations. Could have been hunters, a few said.

Monroe would run into one of the Beesons. None of them had been out that night hunting. This didn't mean it wasn't somebody else, but if it was, it was people none of them knew.

Other family members heard the story and said nothing.

When they told Grandma Sarah, she had questions.

"They were marching?" she asked.

"Yeah," said Grover. "They marched like soldiers."

Grandma Sarah didn't say anything for a long time. She sat looking at her great-grandson—a child she didn't take to be a liar.

Breaking the silence, she said, "What color were their clothes?"

Grover hadn't given much attention to their color. It was hard to tell in the dark. His gaze had been on the guns.

"I dunno," he said. "Maybe gray."

Grandma Sarah nodded. "Sounds like you already know what you saw," she said.

It was years before Grover and Monroe would call what they saw that night "haints."

And years before admitting they’d come across a pair of ghost soldiers, marching to nowhere, under the light of the moon.