I almost missed the road, my brake lights surely scaring those behind me as I abruptly cut the wheel.

I’m on this street for only a second before having to make another sharp turn into an empty parking lot filled with potholes, which fling me like the aggressive rapids of the Chattooga River. I shake, rattle, and roll to a stop. Stepping out of my ride, I regret not bringing a bucket of tar to make the next victim’s entrance a little less adventurous. A prayer for traveling mercies will have to suffice. I say one laced with colorful language as I walk into my destination.

It’s lunchtime, and I’ve brought my appetite with me.

Golden India is the kind of spot you don’t discover on your own—somebody has to tell you. Maybe a local food enthusiast consumed with finding the obscure, or a Wake Forest University college student whose meal card has been maxed out. The invitation might come from a handful of places.

For me, it was extended by a fellow named Don.

Don was a friend of a friend, a person I was told I absolutely had to meet when I moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He wasn’t so much placed on my radar as he was pulled from the shelf like a jar of what George Jones used to sing about. I would soon learn that Don’s presence, like the Possum’s “White Lightnin’,” was punchy and meant to be shared.

The restaurant is nearly empty except for the handful of patrons roaming the aisles of the attached in-house grocery. Grabbing a booth, I watch hands toss lentils, flatbread, and at least one bag of Lay’s India’s Magic Masala potato chips into a small handcart. I’ve never been accused of possessing a sommelier’s nose, but the smells wafting through the room are so distinct, so enchanting, that picking up hints of coriander and ginger takes little effort. I don’t bother with the menu. I’ll eat whatever the server brings. Curry, vindaloo, samosas—it doesn’t matter. Put it in front of me, and I’ll take it down and ask for more.

“You don’t know who Will Campbell is? Do yourself a favor: don’t tell anybody you’re a damn Baptist until you read him.”

Unlike Pavlov’s dogs, I’m already salivating when I hear a ding. A man I take to be Don saunters through the front door. His salt-and-pepper hair is secured in a tight ponytail running down his back. His beard freely wanders. He’s wearing a pair of timeworn overalls that could walk themselves if they had to.

Don slides into the seat across from me, and we go through the motions of Southern salutation. It doesn’t take long to see why our mutual friend wanted us to meet. We go back and forth, discovering our stories intersect regularly, starting with the influences of our Appalachian upbringings and ending with our reluctant roles as misfit ministers to the people known as Baptists.

Over bowls of Indian chutney, we swap “call stories,” an expression ministers use to describe their divine acceptance of their particular purpose. Don tells me how he left a cushy denominational position to till soil, grow food, and give it away. Pausing after a bite of naan, he shares what ultimately led him to the decision: his faith, a few convictions, and the words and work of such people as Kentucky’s farmer/poet Wendell Berry and a man named Will D. Campbell.

He glances up, searching my face for a sign of recognition. Seeing none, he sits his fork down and raises an eyebrow.

“You don’t know who Will Campbell is?” he asks.

“No, never ran across him,” I offer back.

If seriousness was hot dogs, Don’s gaze at me would choke Joey Chesnut, the guy who wins all the eating contests.

“Do yourself a favor: don’t tell anybody you’re a damn Baptist until you read him,” he says.

My hand gets busy writing down the name; I do not yet know my life has just changed. Meeting the right people, at the right time, in the right places is like a game of roulette. Sometimes, we get close, but we rarely beat the house and collect any long-lasting winnings. Be it Don or the Holy Muse working on his behalf, I will soon discover I have hit the jackpot.

Several days later, a copy of Campbell’s memoir Brother to a Dragonfly arrives in my mailbox. The book chronicles Will and his older sibling, Joe, and their closeness by blood and bond. Separating their lives is impossible; to speak of one is to witness the other. I consume it like a starving man does a loaf of bread. Moved to tears by every page, I’m drawn to Campbell’s ability to write about a people who are my own—rural, working-class, Southern whites. Those who often wear poverty, obstinance, and hardships like badges of honor over their eyes, leaving them incapable of seeing the same challenges in the lives of others with different complexions.

For the next few years, I mined for every book, article, and scrap of paper to which Campbell’s name was attached. I'd read about his rearing in Amite County, Mississippi. How in his youth, he brushed up against death, coming down with a severe case of pneumonia. His family would pray and barter with all manners of heavenly hosts to spare his life. Campbell believes this sets him apart in service to God’s will. How, as a medic during World War II, he got his hands on a copy of Freedom Road, a work of historical fiction about race relations in the South during Reconstruction, by Howard Fast. That as a young and aspiring Baptist preacher, he snubbed the expected halls of Southern Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, for the ivy walls of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Then came the short stint as a congregational minister in Louisiana, where his sermons on desegregation and racial reconciliation won him pats on the head but drew few eager souls to join him in those troubled waters. Departing his first and only church, he landed at Ole Miss as University Chaplain. Likewise, his time at the school would be short-lived: his invitation to Alvin Kershaw, a white Episcopal priest and NAACP member, to speak during Religious Emphasis Week raised concerns from the school’s higher-ups. Campbell garnered more attention off the Oxford campus when he and a local African American minister were seen playing table tennis together at the YMCA. This resulted in him waking one morning to find a pile of ping pong balls painted black and white on his front lawn. The writing on the wall came when Campbell discovered human feces covered in powdered sugar floating in a punch bowl during a school-sponsored mixer.

A position he thought would last the rest of his life dissolved in the blink of an eye.

My mother is surprised to see my grandfather holding a Bible. While his sisters, my mother’s aunts, are regular churchgoers and scripture readers, Bun Stigall is not. His Sunday mornings see few pews, and when others convene for Wednesday night studies of the Old and New Testaments, he’s soaking in the testimony of the stars and heat lightning. In one of many fold-out chairs, he gathers with his community—his church—whose congregants are fellow tobacco farmers and dog traders.

“I got Jack something,” he says, holding the book out to her.

He calls me Jack, even though my name is Justin. He never called anyone by their given name. He calls my sister “Sister.” My mother is Little Nance or Nancy Lou. Her name is Penny. When she has me, she becomes Mamie. My father is always Cox, never Marty.

“He’s only four, daddy. Why in the world would you get him a Bible?” she asks back.

“Because Jack is gonna be a preacher one day,” he informs her. This ends the conversation, but the words spoken on my life will ripple forever.

The next time I went to church, I wanted to carry it with me. I knew enough to know my name was supposed to go on one of the front pages. I couldn’t find a pen or a pencil, so I wrote my name in orange crayon. My mother lovingly scolded me.

“He’s only four, daddy. Why in the world would you get him a Bible?” she asks.

“Because Jack is gonna be a preacher one day,” he informs her.

Years later, I’m talking with my cousin Bill at his tire shop. He tells me, “You know, Maw-maw always wanted a preacher in the family. I’m sure glad it was you. I was worried for a while that they would try and put that on me.”

The Bible is my first. Faux leather. Issued by the authority of King James. A bulletin marking the first Sunday I preached a sermon is pressed into the spine. A few obituaries of family members are too. A cutout of my great Aunt Minnie’s hand holds the place of 1st Corinthians 13. She made it while living in the rest home after her dementia got to be too much. A picture of her face rests in the palm like a stigmata, proving her beatification. I use the scripture, words attributed to the Apostle Paul—“Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud…”— at her funeral.

And although worn, my orange-printed name is still there. Still legible.

People ask all the time how preachers wind up doing what they do.

Some come back from the grip of death, receive healing, and are prayed into the role by those who love them. Given to God to serve.

Others are prophesied over by a tobacco farmer.

Either way, the work gotta get done.

Free of steeples and academic quads, Campbell becomes an advisor for the National Council of Churches during the 1960s, aiding their Department of Racial and Cultural Relations. He’s on the ground, behind the scenes, in places like Little Rock and Birmingham during the thick of the Civil Rights Movement. Planning and putting tension on the dividing walls that segregate schools, restrooms, and lunch counters. He’s the only white man present at the inaugural Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At the beginning of the 1960s, he becomes the director of the Committee of Southern Churchmen, a group working with African American communities in the South to bring about social, economic, and political change.

Campbell’s activism continues and grows, branching off in an unforeseen direction following the death of his young friend, Episcopal seminarian Jonathan Daniels. In the summer of 1965, Daniels was in Alabama helping with voter registration. Along with others, he was arrested but was released shortly afterward. Leaving the jail, Daniels and company enter a small grocery store to grab something to drink. A local deputy named Thomas Coleman approaches the group. They exchange words, then Coleman savagely opens fire with his shotgun. Daniels would die at the scene.

Hearing the news while sitting with his brother Joe and friend P.D. East, a Mississippi newspaper editor, Campbell is asked by East if he wants to amend his definition of the Christian message: “We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway.” East asks him if Daniels is a bastard?

“I said I was sure that everyone is a sinner in one way or another but that he was one of the sweetest and most gentle guys I had ever known.”

East doesn’t let up.

“But was he a bastard? Now that’s your word. Not mine. You told me everybody is a bastard. That’s a pretty tough word. I know. ’Cause I am a bastard. A born bastard. A real bastard. My Mamma wasn’t married to my Daddy. Now by God, you tell me, right now, yes or no and not maybe, was Jonathan a bastard?” After a moment, Campbell whispers a yes.

He would sit at the hospital bedside of James Meredith, the first African American student at Ole Miss, after he was shot during the “March Against Fear” demonstration. He then went and visited the man who pulled the trigger, Aubrey Norvell, in his prison cell.

Satisfied, East then asks about Thomas Coleman. Campbell’s yes comes a lot quicker.

“Okay. Let me get this straight now. I don’t want to misquote you. Jonathan was a bastard. Thomas Coleman is a bastard. Right? Which one of these two bastards do you think God loves more? Does he love that dead little bastard Jonathan the most? Or does he love that living bastard Thomas the most?”

Rising from his chair and walking past East, Campbell stares out a window. Through tears, he begins to laugh.

“I was laughing at myself at twenty years of ministry which had become, without my realizing it, a ministry of liberal sophistication. An attempted negation of Jesus, of human engineering, or riding the coattails of Caesar, of playing on his ballpark, by his rules and with his ball, of looking to government to make and verify and authenticate our morality, of worshiping at the shrine of enlightenment and academia, of making idol of the Supreme Court, a theology of law and order and of denying not only the Faith I professed to hold but my history and my people—the Thomas Colemans. Loved. And if loved, forgiven. And if forgiven, reconciled.”

Will Campbell, a man who marched with King, John Lewis, and Bayard Rustin, now begins working as an unofficial on-call chaplain for members of the Ku Klux Klan. He shares a communion of whiskey with Bob Jones the night before the Grand Dragon of the North Carolina Knights heads to federal prison for contempt of Congress. He damn near starts a riot in Atlanta when he tells an auditorium full of students that he’s pro-Klansman because he’s pro-human being. Never supporting their actions or upholding their beliefs, he wasn’t pro-Klan—he just believed if you loved one, you had to love them all.

He lived this expression, his simple mantra. He would sit at the hospital bedside of James Meredith, the first African American student at Ole Miss, after he was shot during the “March Against Fear” demonstration. He then went and visited the man who pulled the trigger, Aubrey Norvell, in his prison cell. He would do the same for James Earl Ray, the man who murdered his friend, Martin Luther King, Jr. Campbell’s message was stripped of any pretense and required no vetting, contracts, or titles. The gap between sin and salvation was too small, or at least too hard to tell apart. The kin-dom of his God, a lowly Galilean, was infuriatingly inclusive, and because of this, the more he shared it, the more he himself was excluded. So goes the life of a bootleg preacher.

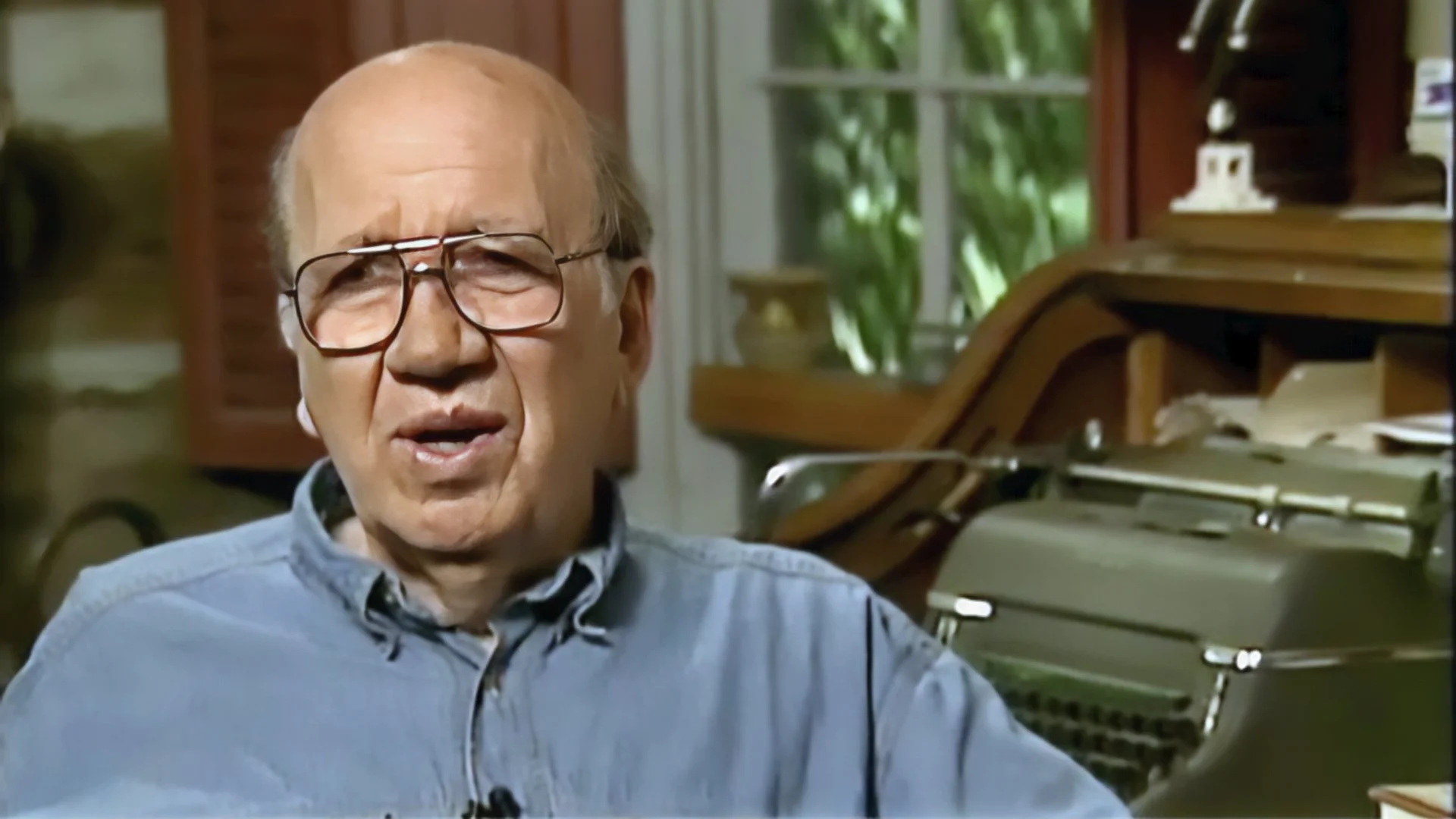

The Rev. Ralph David Abernathy with Will Campbell in 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, only hours after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The evening I get a call from the pastoral search team, I’m alone in my tiny apartment. Over several weeks, what began as an exchange of emails with the committee chair has turned into phone calls. Then, the phone calls become in-person, sit-down meetings.

“We’re going to recommend you to the congregation,” she says.

I get through the rest of the conversation, stammering my way through thank yous, and say goodbye.

I sink to the floor and weep. Part of me is relieved to be chosen, to be on a path that will take me away from the bland existence of shift work in factories. I want to get up; I want to call my fiancée and tell her the news. I want to call my parents and tell them Paw-paw was right, but I can’t. A weight as heavy as a cast-iron skillet keeps me from moving.

I study theology and church history. I read scripture in its original languages. I get educated. I learn lessons beyond what is taught in Sunday school. The exposure creates a chasm between me and the people I’m supposed to love. Old deacons say, “Don’t go to seminary, son. It will rob you of the faith. It will snuff out your fire.”

My fire, my faith, does get smaller, but it’s only because I’m aware that other burning bushes exist all around me.

Before leaving that church, the people there ordain me in the Baptist way. I kneel before the congregation, and they come forward to lay hands on me one by one. I feel some of them attempting to squeeze what they have of the Holy Ghost into me. When the service ends, they hand me a Bible and a paper with a dozen signatures, affirming my call to Gospel ministry. It’s the only credential I have hanging in my current church office. I look at it often and wonder if the names on it would sign it today.

Time passes. I’m with Don again, this time in a Waffle House. I tell him I think congregational ministry will be hard on me. He tells me he’s glad I’m figuring that out now.

From the 1970s on, Campbell continued to write, and his status as a shit-stirring folk hero grew. Stories about him would be told by all sorts of people. Southern writers like Walker Percy and John Egerton. Country music royalty such as Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, and Jessi Colter. Fellow ministers William Sloane Coffin and Billy Graham. And at least one president of the United States, Jimmy Carter. Accounts from these sources are well documented.

And then there are the others. Heard in contrarian circles from other venerated agitators. Tales of how Campbell was seen walking around the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention in the early 1990s. This was during the Conservative Resurgence/Takeover, where moderate to progressive leadership within the convention was systematically removed from office. Campbell had long distanced himself from SBC life, claiming he was not a Southern Baptist but a Baptist who happened to be Southern. When approached and asked what in the world he was doing there, so out of his element, surrounded by fundamentalists, Campbell responded, “I’ve come to watch a denomination die.”

Or the anecdote about Brother Will stepping onto a stage to receive an award from a group he took to be “lukewarm” Baptists.

“I’m told I’m standing in the presence of a bunch of moderates,” Campbell says. The few chuckles are cut short when he clears his throat and spits off the side of the stage. It would seem Brother Will is a Biblical literalist, at least when it comes to Revelation 3:16.

He was a prophet for a South that desperately needed him then and could use more of him today.

Such actions would earn him praise, which he would spurn. Accolades would be extended to him, which he openly abhorred. Bring up anything resembling personal achievement, and he’d sidestep with the grace of a Spanish matador.

Will Davis Campbell released his spirit in the summer of 2013. He is remembered as a force of a nonconforming nature trapped in modest flesh. As an iconoclastic shaker of the status quo. A challenger of institutions. A critic of TV evangelists, labeling them “electronic soul molesters.” He was a prophet for a South that desperately needed him then and could use more of him today. A bloodhound who heard a whistle others couldn’t or refused to—a call to “be ye reconciled” to Maker and neighbor.

Why more people don’t know about Brother Will, I do not know.

I often wonder where the kinship I feel toward Brother Will comes from. I ask my spouse Lauren this question. She smirks and asks me, “What did you write on the application for that big scholarship a few years ago when you were in seminary? What was your answer to the question about what that money would allow you to do if they gave it to you?”

I told them it wouldn’t allow me to do anything other than what I’d planned to do. In so many words, I explained my vocational call would not be determined by any monetary means.

“And the time you looked at having your ordination recognized? How’d that go?” she asks.

When we first migrated to New England from North Carolina, I sat in front of a group of Baptist ministers from a tradition different than the one conferring my grassroots holy orders. They asked me why I thought I needed my ordination acknowledged by them. I told them I didn’t need it but thought it would be nice. When they asked me what I thought about why Jesus had to die to save humanity from God’s justifiable wrath, I paused before offhandedly saying, “I don’t. I don’t think about it one second because I don’t hold to a belief God would do such a horrible thing.” They weren’t surprised when I told them I didn’t see the Bible as being free of error. All parties left the meeting with smiles as empty as my grandmother’s cookie jar.

When they asked me what I thought about why Jesus had to die to save humanity from God’s justifiable wrath, I paused before saying, “I don’t. I don’t think about it one second because I don’t hold to a belief God would do such a horrible thing.”

Lauren nods. Before leaving the room, she says, “You secretly enjoy doing stuff like that.”

Why Will? I’m starting to believe we search for similar voices and seek pens that inspire us to use our own. Brother Will’s hands push my pencil and help me awkwardly pound on a keyboard. His life reminds me of why I don’t want a perfectly curated faith and why I’ll never be what many think a minister is supposed to be. He lets me know I’m not alone.

“Do all Baptists think like you?” The question comes from the choir director at my church. He’s young, passionate about music, and highly talented. I tell him what I think about a literal hell existing and why I don’t think any of us are going to end up there, because God’s scandalous love will not allow it.

“Do all Baptists think like you?”

“No, not all Baptists think like me,” I say.

Just some of them.